Building a change agent network

The importance of change agents

If you’re involved in rolling out a significant organizational change you are likely to require a network of change agents (often called change champions) to help you get it done. Furthermore, it’s widely held that to achieve significant change, employees need to hear about it from at least 2 different sources.

Firstly, from someone senior in the organisation to position the change, enabling them to understand the importance of it, and then also someone ‘closer’ to them in the organisation to help put the change into a more localised context. This is where line managers and change agents come into play, and there are many considerations when building a network of change agents.

How many change agents do I need?

There are several aspects just for this question alone. First you need to understand the breadth of the change. How many departments, roles and people are going to be affected, and how difficult or extensive is the change? Some changes just require relatively simple compliance, maybe with a new system, or process it may be primarily about training, but there are other changes that require a deeper level of adoption, especially when we are talking about a cultural shift. If it’s a cultural change people need to internalise the change and be able to make different work / task-related decisions on the back of their understanding and a changed mind-set.

Something else that will affect the size of the network required is how long it’s likely to take to roll-out the change, and what is required of change agents for this particular change? Is involvement likely to vary between departments? Will change agents have to train others thus needing to become fairly expert in what it is first? Are they going to need help with soft skills because of the anticipated levels of resistance? Are they going to be full-time or part-time change agents and therefore what’s the impact on their business areas? Is it going to be better to have one person with 100% of their time dedicated to the change against 5 people with 20% of their time allocated? Whilst it might be easier for a for a change manager to have to communicate with one dedicated full-time resource over 5 part-time people, it’s possible that you won’t have a choice because of the impact on BAU and the breadth of departments to cover. So many things to consider!

Some change consultancies do like to suggest a ratio & I’ve often seen something like 1 to 60 or 1-100 (change agents to change targets). Such ratios are often given on the basis that the role is a part-time one, maybe giving over 10% of their time. Whilst such a ratio might be a helpful start-point, every change is different, so the scale of the network requires thought.

Who to get involved?

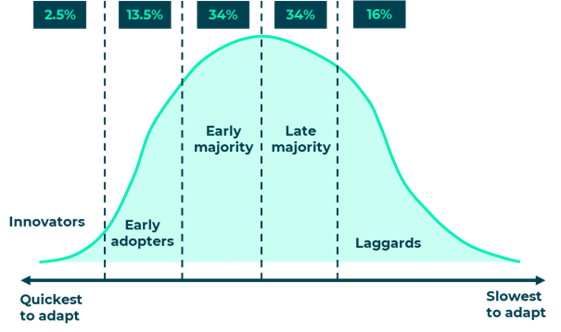

This is possibly the most vital question! Here we can draw on E.M. Roger’s ‘Diffusion of Innovation’ theory developed in 1962. The theory explains how (over time) an idea spreads and ultimately gets adopted throughout a population. The theory (also referred to as Roger’s Innovation Adoption model) breaks down a population into 5 key adopter groups as some people / groups are more receptive to adopting something quicker than others.

The group Roger’s calls ‘Innovators’ want to be first to try things out. These are people who may be found in a midnight queue to get the latest tech the moment it becomes available. Nothing needs to be done to encourage this (small) group. The next group Roger’s coins ‘Early Adopters’ who represent opinion leaders and tend to enjoy leadership roles. They are likely to be ‘on the ball’ with change, possibly already understand the need for the particular change. It may be sufficient for this group to just provide information regarding implementation, again with little need for encouragement to embrace the change.

How is this pertinent to change agents? If the innovators and early adopters are identified they could be recruited as change agents to help bring the majority along, especially if they are well respected thought leaders amongst the community. Indeed, one of the stakeholder engagement principles within APMG’s Change Management qualification states ‘some stakeholders are best engaged by others’. It’s about identifying who the optimum ‘others’ are.

Line managers are an important group within your community who will themselves need representation and support to enable them to be at the front line during a change, but there are issues with using line managers as change agents. Not least is whether or not they have enough time to do justice to the role. They must balance the duality of business as usual with the demands of change so they may be pre-occupied with how changes affect day-to-day business rather than the resultant benefits. Of course, line managers have an association with the way things currently work and may find it challenging to disturb and challenge current ways of working or even feel a certain amount of resistance to the change themselves but have a ‘duty’ to maintain an outward promotion of the change whilst supressing their personal reservations. They may also have concerns about losing control and status.

Whilst you may recruit some of your line managers as change agents, it is usual to embrace broader representation. The options are to recruit internally (front-line / street-level professional) change agents from within your change target community (we could call these local change agents) and / or external change agents, whom we could call ‘pro’ change agents. Let’s examine the advantages and disadvantages of each.

Using (and Recruiting) Internal Change Agents

It’s often said that the best change agents for the line are usually the best people from the line. You are looking for people who have a good understanding of current ways of working, even seen as subject matter experts, but coupled with a desire to make improvements and the right interpersonal skills. They should be receptive to change, not be set in their ways.

There are many advantages in recruiting internally, not least of which is that internal change agents already understand internal procedures, the prevailing culture and internal politics; and they are usually relatively quick to second over to a change team. Another good thing about using internal change agents is that they should be appointed based on having local credibility / are trusted by their peers. Working in a change agent capacity is often regarded as a development opportunity by internal people who have not done it before.

However, on the downside you need to ask how much time will they be able to give to the change, can they be completely taken away from their ‘day-job’ for a period? Sometimes acting as a change agent results in people being a bit outcast by their peers and subsequently seen as ‘one of them’. Also, if they haven’t acted in this capacity before they may not have the necessary inter-personal skills and confidence to take on the role. Of course, people with the right aptitude can be trained.

It is a common mistake to just go for whoever is most readily available and / or most technically knowledgeable because they might lack the softer skills (or potential to develop the softer skills) required. Sometimes you find people like the idea of the role and volunteer for it, receive training but then lack the courage to carry it out effectively.

How then to appoint internal change agents and make sure you get the right people? There are a couple of options. You could ask for volunteers (but you may not get the ‘right’ / optimum people) or alternatively select and appoint individuals who have the right technical and interpersonal skills (but they may be reluctant to do it). Be aware that when you ask for volunteers you may get people with a hidden agenda who volunteer because they actually want to disrupt things.

The best way can be to both ask for volunteers and back it up with recommendations. For example, when I first become a change agent some 20 years ago for a major insurer, a request was put out for volunteers, but the volunteers also had to be nominated by a couple of peers. This pragmatic approach seemed to work well, but I suppose I would think so as I got the gig! Be aware that if you do ask for volunteers, you need to position the role well, ideally create some sort of a ‘buzz’ about the initiative, but you should also have a fall-back plan in case you don’t get sufficient volunteers. One method is to use the ‘snowball’ technique, asking those who do come forward to nominate 5 people, and then ask each of them to nominate another 5 and so on. Good questions to ask are: ‘who would you go to for advice’ and ‘who do you trust’?

Using external change agents

For a major change initiative, the ideal scenario is to have the majority of change agents being internal, but to also include a few external change agents to bring in specialist change expertise if you have the time and budget to do so. Of course, in this case you can recruit in exactly the skills and knowledge that might be lacking internally and use the outside experts to help up-skill your internal resources.

External change agents are sometimes referred to as behavioural scientists, people who specialise in human behaviour. They will already understand what is expected of the role and should be recruited on the basis that they are comfortable with ambiguity, have the right soft skills, and dare we say it charisma. They should be able to handle resistance to the change and have a certain amount of resilience themselves.

Advantages of external ‘pro’ change agents are that they offer a fresh perspective and have no allegiance or emotional attachment with the past and any existing processes and procedures. As professionals they are not going to be cynical about the need for change. It can also be the case that outsiders’ opinions are more respected by those you need to make the change just because they are outsiders and have a perspective broader than just this organisation.

The downside of recruiting externally is that it can take time, you may have to allow for notice periods, they won’t be aware of nuances of organisational history, culture and therefore be able to easily anticipate the likely resistance. They will need induction in local processes and systems and the organisational structure. It can also be the case when using external change agents that staff feel that the change has been ‘done to them’ and imposed.

Final Thoughts

When recruiting change agents, it’s important, especially for a complex and lengthy changes, to build in a certain amount of contingency regarding numbers of agents and consider succession planning or even a ‘pipeline’ of agents. After trying the role out some people may feel that it isn’t for them and request to revert to their ‘day job’, and others who take to it and shine may get offered new, more exciting positions before your change is complete.

When selecting internal change agents, you need to be aware that line managers are going to be losing some of their capacity so there could be a requirement to back-fill those positions or maybe hire temporary staff. Of course, line managers should be encouraged to view this as an opportunity for their staff.

Once you have assembled your team you will need to train them and / or induct them into the company and then the change manager will need to make sure the agents work together well as a new team, but more on building a good team another day.

Finally, if you aren’t sure of exactly what it is a change agent does here’s a link to help ‘What Makes a Great Change Agent'.